ROMANOV FAMILY AND RASPUTIN

By Amanda Madru

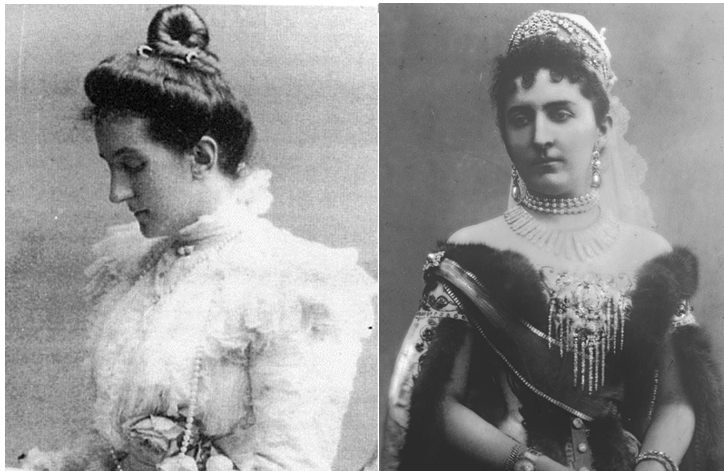

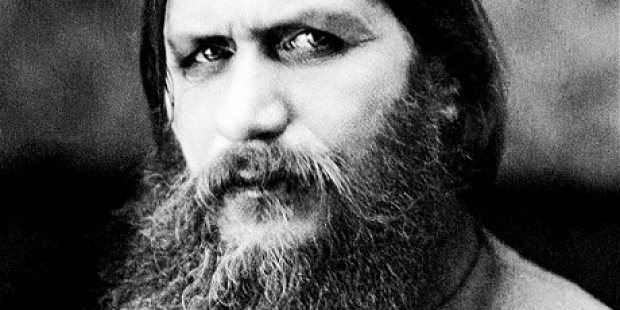

Grigory Yefimovich Rasputin is a magnetic specter in the drama that is Russian history, for the peasant mystic from Pokrovskoe played a defining role in the last days of the Romanov Dynasty. In 1905, the fateful meeting took place. Rasputin requested—and was granted— an audience with the Romanov family at Peterhof, where he presented them with a hand-painted wooden icon of Saint Simeon, a venerated Siberian saint dear to Rasputin’s own heart. He soon became a trusted advisor and confidante to Emperor Nicholas II and Tsaritsa Alexandra Feodorovna; Alexandra in particular was convinced that the “staretz” was a gift to her from God Almighty, sent to ease her passage through life as the “Little Mother of Russia,” and especially to preserve the precious life of her only son, the Heir, Tsesarevich Alexei Nikolaevich.

Impressed as Nicholas II and Alexandra were with the “Russian peasant,” members of the extended Romanov family, sensing that something was not quite right, were less than pleased with the Tsaritsa’s ever-increasing reliance on his counsel. She credited his prayers with saving Alexei’s life on more than one occasion, and she taught her children to view Rasputin as their “Friend.” Nicholas II’s sister, Grand Duchess Xenia Alexandrovna, strongly disapproved of this familiarity, especially after learning from governess Sofia Ivanovna Tyutcheva—who was fired by the Tsaritsa for her troubles—that Rasputin was granted access to the nursery when the four grand duchesses were in their nightgowns: “…the attitude of Alix and the children to that sinister Grigory (whom they consider to be almost a saint, when in fact he’s only a Khlyst!) He’s always there, going to the nursery… he sits there talking to them and caressing them. They are careful to hide him from Sofia Ivanovna, and the children don’t dare talk to her about him. It’s all quite unbelievable and beyond understanding” (Maylunas, Andrei, and Mironenko, Sergei, A Lifelong Passion: Nicholas and Alexandra: Their Own Story 330). The girls’ youthful favorite aunt, Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna, met Rasputin in 1907—she was taken to the nursery by her brother the Emperor, where Rasputin was with the children, who were clad only in nightgowns. “All the children seemed to like him,” the seemingly skeptical Olga Alexandrovna recalled. “They were completely at ease with him” (Massie, Robert K. Nicholas and Alexandra 199).

If the Imperial children were at ease with Rasputin, few others were. In 1910, one of their nurses, one Maria Ivanovna Vishnyakova claimed that the “Holy Man” had raped her, but the Tsaritsa refused to believe the woman’s story. Supposedly, Vishnyakova’s allegations were investigated, but little came of it, as her credibility was damaged when she was caught in bed with a Cossack of the Imperial Guard, (Radzinsky, Edvard. 139) and three years later, she was dismissed from her post.

The following year, 1911, things got even worse when the Montenegrin sisters, Grand Duchesses Militsa and Anastasia, wives to Grand Dukes Peter and Nicholas Nikolaevich, learned that Rasputin was engaging in illicit liaisons with various St. Petersburg women, and they went to Tsarskoe Selo to warn the Tsaritsa. Alexandra, however, refused to believe that the “staretz” was anything but holy. Then, the Inspector of the Theological Academy, Bishop Theophan, who had until then been impressed by Rasputin’s apparent faith, began hearing confessions from the women who had been with Rasputin. He too went to the Tsaritsa and warned her that the peasant from Pokrovskoe was something less than sanctified. Alexandra heeded her former confessor’s advice and sent for Rasputin, demanding an explanation, but he feigned surprise and professed his innocence. Bishop Theophan was then sent away to the Crimea for daring to speak against Rasputin.

Next, the Metropolitan Anthony attempted to speak to Nicholas II himself, but the Emperor too was not open to listen; he insisted that the Church was not to concern itself with the private interests of his family, but the Metropolitan informed him that “…this is not merely a Romanov family affair, but the affair of all Russia. The Tsarevich is not only your son, but our future sovereign and belongs to all Russia” (Massie 209). Perhaps Anthony could have been a voice of reason, a saving grace, but soon after this conversation, he fell ill and died.

The powder keg exploded when Rasputin boasted to a monk named Iliodor that he had kissed Tsaritsa Alexandra. Iliodor did not believe him, but then Rasputin showed him various letters written by Alexandra and her children (three years later, these letters went public and were viewed as “evidence that Rasputin and Alexandra were lovers). Iliodor was shocked, and he kindly encouraged Rasputin to mend his ways—until it came to light that Rasputin had attempted to rape a nun. When the charges became known, Nicholas and Alexandra (the latter still professing the innocence of the “Holy Man”) were forced to distance themselves, and Rasputin fell out of favor in aristocratic circles.

It would be a year before Rasputin would reenter the lives of the Romanov family. In October of 1912, the Imperial couple and their children were on retreat at Spala, the traditional hunting lodge of the Polish kings. It had been two weeks since hemophiliac eight year old Tsesarevich Alexei had gone rowing, falling in the boat and bruising the upper part of his left thigh, Dr. Botkin, the court physician, had ordered that the Heir stay in bed. A week later, the pain and swelling were much diminished, and the incident was over. Or so everyone thought.

During his recovery from the fall in the boat, Alexei began French lessons with Swiss tutor Pierre Gilliard. Gilliard was as yet unaware of the precise nature of the Tsesarevich’s ailment, but he certainly knew that the boy was not healthy. He recalled that he “looked… ill from the outset. Soon he had to take to his bed… I was struck by his lack of color and the fact that he was carried as if he could not walk” (Massie 182).

Alexandra, thinking that a little fresh air and sunlight might revive her son, then made the catastrophic decision to take the Tsesarevich for a carriage ride. Alexei began to complain of severe pain in his leg and abdomen. Alarmed, his mother ordered the driver to return to the hunting lodge; however, they were several miles from the villa, and the sandy road was rutted and uneven. It wasn’t long before Alexei began to cry out at every jolt and lurch of the carriage; Alexandra, in terror by now, first implored the driver to hurry, and then to proceed slowly and with caution. Her companion, Anna Vyrubova, who had accompanied the Tsaritsa and her son on their outing, described the return trip as “…an experience in horror. Every movement of the carriage, every rough place in the road, caused the child the most exquisite torture and by the time we reached home, the boy was almost unconscious with pain” (Massie 182).

Alexei’s father, Nicholas II, wrote that “The days between the 6th and the 10th were the worst. The poor darling suffered intensely, the pain came in spasms and recurred every quarter of an hour. His high temperature made him delirious night and day; and he would sit up in bed and every movement brought on the pain again. He hardly slept at all, had not even the strength to cry, and kept repeating, ‘Oh, Lord, have mercy upon me” (Massie 182). There was, however, no mercy in sight—for days, Alexei’s cries and screams echoed through the hunting lodge halls. He begged his mother, “Mama, help me. Won’t you help me?” (Massie 183). His pleas were for naught: there was nothing for the Tsaritsa to do but pray. She too had no rest; she could only look on helplessly as “Baby” continued to suffer.

Nicholas and Alexandra were certain their son was dying. Indeed, Alexei himself would have welcomed death: “When I am dead, it will not hurt anymore, will it, Mama?” he asked (Massie 183). His mother, although she never gave up hope for a miraculous healing, was forced to live with the knowledge that it was she who had passed the curse of hemophilia on to her beloved child.

Alexei’s disease was a state secret, and circumstances were precarious: the hold of the Romanov Dynasty on the throne of Russia was tenuous at best, and the Tsaritsa was an unpopular consort who would certainly have been blamed for her faulty bloodline; it was determined that it could not be publically acknowledged that the heir—the only heir—was so afflicted as to be unlikely to see his twentieth year. There were rumors, of course, and speculation, but the true nature of his disease was rarely, if ever, disclosed.

In spite of the publicity machine’s efforts to keep this dark secret a secret, reports began to surface that something terrible had happened to the Tsesarevich. Gossip flew through St. Petersburg society, and it was only after the doctors warned the distraught parents that the continuing hemorrhage in Alexei’s abdomen could end his life at any moment that bulletins were released to update the public, but even then, the cause of the hemorrhage was not revealed. Still, all of Russia began to pray for the boy expected to be their Emperor. When it seemed clear that the end was imminent, Alexei received the Sacrament of Extreme Unction, and a news bulletin sent to the capital was phrased in such a manner that a following notice could make the dreaded announcement that the Heir had expired.

In desperation and at the end of her rope, Alexandra Feodorovna turned to her one remaining hope: Grigory Yefimovich Rasputin. She bid Anna Vyrubova to send a telegraph to Grigory’s home in Pokrovskoe, entreating him to pray for the Tsesarevich. The prophetic reply was immediate: “God has seen your tears and heard your prayers. Do not grieve. The Little One will not die.” One day later, the hemorrhaging ceased.

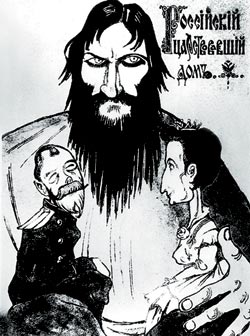

From that moment on, the position of Grigory Rasputin within the closed circle of the Romanov family was firmly cemented. Rumors of his debauchery continued to swirl, so much so that at times—much to his wife’s displeasure—Nicholas had no choice but to keep him at arm’s length. Alexandra continued to believe that the “staretz” was a living saint, even when the director of the national police informed her that an inebriated Rasputin had exposed himself in public and announced to the patrons of a crowded restaurant that Nicholas allowed him to have sex with his wife whenever he pleased. Alexandra wasn’t the only target, though—it was whispered that Rasputin had also seduced the grand duchesses. “Saints are always calumniated,” she insisted. “He is hated because we love him” (Denton, C.S. Absolute Power 577). Nicholas capitulated to Alexandra’s wishes because he felt he had no other option: after all, Rasputin had the ability to ease Alexei’s suffering and keep the boy alive. Gilliard wrote in his memoirs that, tragically, “Nicholas did not like to send Rasputin away, for if Alexei died, in the eyes of the mother, he would have been the murderer of his own son” (Gilliard, Pierre. Thirteen Years at the Russian Court).

The outbreak of World War I in 1914 was the beginning of the end for Rasputin, as well as for the Romanovs. Rasputin begged the Emperor—who mistakenly believed that Germany would never simultaneously attack Russia, France, and England—to stay out of the conflict. “If Russia goes to war,” he told Nicholas, “It will be the end of the monarchy, of the Romanovs and of Russian institutions” (Alexandrov, Victor. The End of the Romanovs 155). This time, though, Nicholas II did not heed Rasputin’s advice, and his decision proved to be a fatal one.

The war was disastrous for Russia. Everyone expected it to be over quickly, but a year later, the battle raged on, and more than a million Russian soldiers were killed. The people blamed the already-hated Tsaritsa, believing her to be a spy for Germany, the country of her birth, especially after Nicholas took command of the armies. His decision to do so was certainly influenced by his wife and Rasputin, who firmly supported him, but the consequences of this action were calamitous. Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna, wife of the Emperor’s deceased uncle, Grand Duke Vladmir Alexandrovich, was a vocal opponent of Alexandra, whom she and many others feared would be the supreme ruler of the country in place of her husband.

Gilliard wrote that “…her (Alexandra’s) desires were interpreted by Rasputin, they seemed in her eyes to have the sanction and authority of a revelation.” According to historian Greg King, Rasputin’s influence over the Tsaritsa was such that he manipulated her and the destiny of Russia, while Nicholas executed her will at Rasputin’s behest. Then, a politician by the name of Vladimir Purishkevich became a voice of dissent within in the government. He stood before the Duma and stated that “The Tsar’s ministers who have been transformed into marionettes, marionettes whose threads have been taken firmly in hand by Rasputin and the Empress Alexandra Fyodorovna—the evil genius of Russia and the Tsarina… who has remained a German on the Russian throne… an illiterate moujik (peasant) shall govern Russia no longer. While Rasputin is alive, we cannot win” (Radzinsky 434). Much of Russia concurred.

Prince Felix Yusupov, husband to the Emperor’s only niece, Princess Irina Alexandrovna, was inspired by Purishkevich’s speech. Yusupov conspired with Purishkevich and Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich, Nicholas’s cousin; the three agreed to put an end to Rasputin once and for all.

Yusupov, familiar with Rasputin’s history of womanizing, invited the “Holy Man” back to his family’s palace on the pretense that he would be introduced to the very beautiful Princess Irina. From here on out, though, the details are murky. Yusupov wrote in his memoirs that he plied Rasputin with tea and petits fours, which were laced with cyanide. Soon, Rasputin was quite drunk, and Yusupov, with Grand Duke Dmitri’s revolver, shot the “Mad Monk” point blank—the bullet entered his chest and exited his body on the right side (Nelipa, Margarita. The Murder of Grigory Rasputin: A Conspiracy That Brought Down the Russian Empire 309). Rasputin fell, but did not die. He attempted to escape, but Purishkevich shot him four more times, after which he fell in the snow outside the door. Although the wounds were mortal, Yusupov wanted to be sure, so he shot Rasputin once more, this time in the head. Finally, the conspirators wrapped the corpse, drove it to the Malaya Nevka River, and tossed it over a bridge railing into a hole in the ice.

Rasputin was dead—there could be no doubt, for the murderers had botched the disposal of his body, and he was found washed up on the shore by the Petrograd police—but the spectre of their “Holy Man” would continue to haunt the Romanov family until they were themselves murdered in 1918. Felix and Dmitri claimed they had acted to preserve the dignity of the Romanov Dynasty, but their violent deed perhaps too little, too late. Russia plunged headlong into revolution, and with that, the Empire was swept away forever.

Leave a comment